How I got my first business loan

It wasn’t until calls began coming in from all over the world that Conor Sampson realized he had the makings of an international business success on his hands.

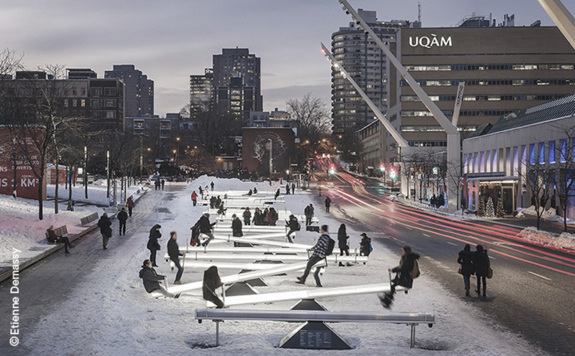

The quirky seesaws his team had designed for Montreal’s downtown festival district had been an instant hit with kids and adults alike. The 30 seesaws light up and emit sounds in unison to create a playful symphony as people go up and down.

The seesaws caught the attention of cities and festivals in other parts of the world and Sampson was faced with a decision. Would he take on debt to capitalize on the attention or let the opportunity slip away?

“We knew we had to do something this year or not do it at all,” says Sampson, who founded his architectural lighting firm, CS Design, in 2008.

But he’d never needed to go to a bank for a loan before and was unsure about how to navigate the process.

“I needed reassurance that this was a viable opportunity before taking out a loan.”

Create a business plan

Sampson isn’t alone. Many entrepreneurs are hesitant to take a business loan, preferring instead to use their day-to-day cash to invest in new projects. Aurore Olszanowski, Senior Account Manager at BDC, says it’s natural to be cautious, but using cash flow to invest in new projects can put undue financial pressure on your business if you hit a bump.

“There is always a level of risk that comes with any investment,” says Olszanowski, who helped Sampson get his business loan. “But preparing a detailed business plan will provide you with a roadmap you can follow to limit your risk.”

Identify an opportunity

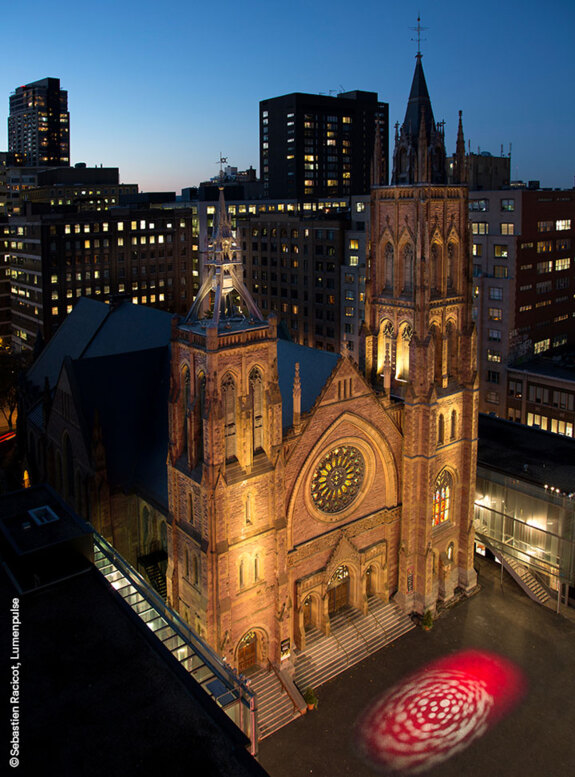

Up to this point, CS Design had created architectural lighting concepts for buildings and public places. The firm had provided design services, without getting into the production side of things.

To make sure the seesaw opportunity was viable, Sampson teamed up with one of his employees, Anne-Marie Paquette, to study the market, make financial projections and create a business plan.

“With the seesaws, we saw we had the competencies and the skill-set to actually make things on our own,” says Sampson. “We could grow to include product design and temporary exhibits.”

Prepare financial projections

The idea was to create a better, more robust seesaw that could improve the experience at long-term installation in public spaces and festivals all over the world. Sampson and Paquette also co-founded a new company for the project—L4 Studio.

The pair sat down with an accountant, who helped them prepare a five-year cash flow projection to show the project was financially viable.

“We realized we would need a large cash injection up front to finance the production of these pieces and exhibit them around the world,” Paquette says.

Consider various sources of financing

Sampson and Paquette considered various types of financing before finally settling on a term loan.

“We were building our revenue model and our business projections, and asking if this would be interesting for venture capital,” says Paquette. “We realized this is going to be a steady, profitable business, but it’s not going to provide the return rates venture capitalists or angel investors typically expect.”

The process of building the business plan and the interest they had received from potential customers reassured Sampson that debt financing was a risk worth taking.

The pair visited several banks before applying for a loan on BDC’s website. Sampson and Paquette eventually met with Olszanowski to present their project.

Their hard work paid off when they received a BDC business loan for the full amount they were looking for.

Have your documents in order

“We came prepared with arguments to show that we have both the knowledge and skills to expand into this market,” Paquette says.

Apart from the business plan, the entrepreneurs also showed purchase orders with specific timelines. And they highlighted their experience creating the seesaws in Montreal, which was co-designed with collaboration with Toronto’s Lateral Office. They’d encountered all the wear and tear that comes with being in a public space.

“We’ve seen people jumping on them,” Sampson says. “We’ve learned what works and what doesn’t and we are able to mitigate the risk as a result.”

Show your network and your passion

Olszanowski says bankers like to see entrepreneurs who are well established. Sampson and Paquette, for example, have been working in their field for over a decade. They were able to show the network of advisors and industry professionals that can support their project.

“Being in Montreal gives us that critical mass of producers to be confident that we will be able to build whatever we design,” Sampson says.

A final ingredient: Sampson and Paquette showed they were passionate about their work and that they believed in this project.

How do you go to work everyday if you are not doing something you are interested in? So much of getting people to buy what you are selling is to get them interested in your vision and what you want to do.

Conor Sampson

Owner, CS Design

3 lessons learned

1. Create a solid business plan

Sampson and Paquette took a full year to study the market, put a money figure on the size of the opportunity and create a business plan. Their plan included five-year cash flow projections to show the project was financially viable.

2. Surround yourself with the right people

You’ll need to find the right advisors such as an accountant and lawyer. But bankers will also want to see that you know key industry specialists that can help you deliver your project.

3. Come prepared

Do you have firm orders in place? What collateral are you ready to offer for the loan? Put yourself in the best position possible by showing you have done your homework and know your project inside out.